Across Florida, long-forgotten cemeteries are being rediscovered, in some cases centuries after being lost to development. One was recently found in Tallahassee. Local historians say the cemetery was for enslaved persons, and has ties to a plantation owned by a powerful family.

Near the tee box of the seventh hole at Capital City Country Club are a number of barely-visible depressions in the turf. Thanks to word-of-mouth going back hundreds of years, modern technology and determined archaeologists, it’s finally been discovered: the forgotten gravesites of enslaved people dating back to the Civil War era.

“There was a big rushing wind that came through. And it kind of blew some people’s hair up, and it blew my coat open and my tie in the air. So, I definitely could feel the presence of the ancestors here,” said Delaitre Hollinger, executive director of the National Association for the Preservation of African American History and Culture, explaining what he felt the moment archaeologists confirmed the sites.

Hollinger, former president of the local NAACP chapter, has taken a keen interest in the discovery. Days after the start of 2020, he came back to the golf course as interest in the find intensified.

“We’re standing on top of a golf cart path, right next to the seventh hole,” Hollinger explains. “The seventh tee is here, there’s another tee there. But according to the technology used to determine what is underneath – all this is built on top of the graveyard.”

For years, Hollinger heard tell of a gravesite for people who were enslaved, but had never known its exact site – until now.

“In February of 2019 I was invited to be on a radio show – on WFSU with Tom Flanagan, to discuss local historically significant African-American properties,” Hollinger recalled. “And there was a caller who called into the show, who asked if those of us on the program had heard of there possibly being a cemetery at the Capital City Country Club.”

From there, he began doing more research. Fast forward to the end of 2019. At the end of last year, National Parks Service archaeologist Jeffrey Shanks took ground penetrating radar technology to the site.

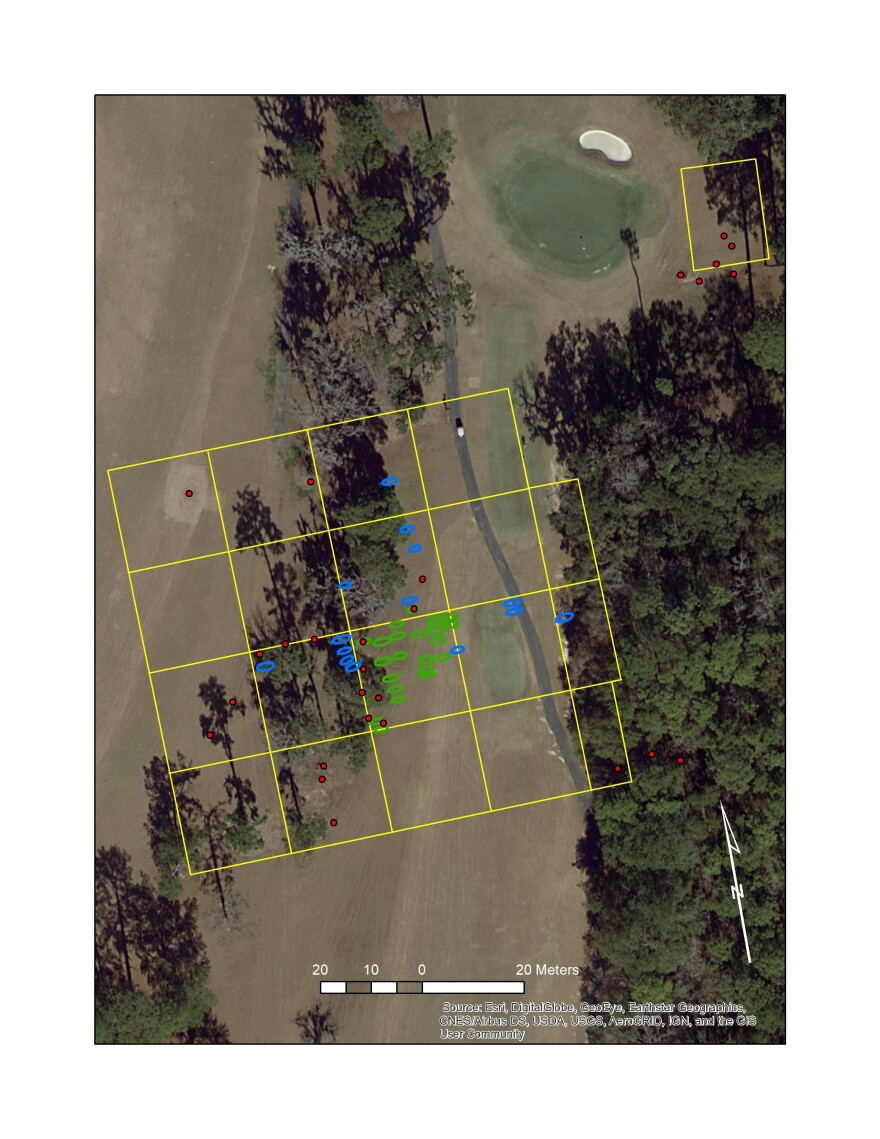

“So, what we’re doing is we’re pushing the GPR unit along the ground here,” Shanks said while demonstrating the technology he used to discover the graves. “It’s shooting radar waves into the ground and bouncing them back up. And as it hit anomalies under the ground it’s recording that, and that’s all being pieced together, stitched together essentially, by this data recorder.”

The resulting images put together gvea Shanks and his team a 3-D model of what’s below the surface.

What Lies Beneath

Some of the anomalies Shanks found are nearly unmistakable as graves, he says. And he's confident there are roughly 40 of them in what would have been a cemetery.

“So it will essentially appear as a rectangular dark blob on the map,” Shanks says of the images he took with the imaging software. “Because it’s three-dimensional, we also have the depth. So, we’ll see this sort of rectangular blob shape about four to six feet below the surface, about the depth you’d expect for a grave. They’re about the size or the length of a grave. More importantly, we’ll see things like rows of these anomalies all together – like you would expect, again, in a cemetery.”

The graves are aligned east and west, which Shanks says is typical for historic burials. For extra certainty, the archaeologists also enlisted the astute noses of highly trained dogs.

“We also have human remains detection dogs that came out, and they alerted in those same areas,” Shanks said. “So that’s just another level of evidence that these are almost certainly graves.”

Uncovering History: The Houston Plantation

Jonathan Lammers helped piece together some of the historical records showing the graves are connected to what was a plantation owned by the family of Edward Houston, a powerful Savannah landowner.

“The Houston family was from Savannah; they were a very prominent family – a leading family of Georgia really. When Tallahassee was opening up, two Houston family members came here in 1826 and purchased a half square mile – that was sort of the start of it, basically where Woodland Drive is today,” Lammers said, standing on the course’s seventh hole.

Lammers wrote a report that helped convince Capital City Country Club to allow Shanks and team to take a look under the ground.

“The report is mainly on the history on the land transactions out here to demonstrate that this is not a cemetery that would have been for whites, this is not a family cemetery for the people who owned the plantation – this is almost assuredly a cemetery for the enslaved people who worked on the plantation,” Lammers said.

Now, he's focused on trying to find possible descendants of the enslaved people who would have lived on the Houston property.

“If there’s anybody in Tallahassee, Leon County or this region, if any of their family members had a last name of McQueen, particularly if they grew up in the Smokey Hollow area, have long-standing roots, I’d be interested to talk to them."

The country club, which began operating as a golf course in 1908, is on land owned by the City of Tallahassee and leased by the Club. The archaeologists and their partners say the City has welcomed their investigation. Jay Revell is a golf writer who is a member of the club and its unofficial historian.

“I think what you’ll see through this collaboration with stakeholders is – we’ll come up with a great way to do an appropriate memorialization that tells that story, and we’ll go through the process, or I hope we’ll go through the process of the Florida Historic Marker,” Revell said.

Tallahassee isn’t the only place rediscovering long-buried history. Forgotten cemeteries have also been found in nearly ten places in Tampa. And a team of archaeologists from The University of South Florida suspect, and are currently looking for, more graves at the infamous Dozier School for Boys.

Florida legislators have taken notice. Tampa Democratic state Senator Janet Cruz has legislation moving in her chamber that would create the state Task Force on Abandoned African-American Cemeteries.

Shanks says the Capital City Country Club isn’t even the first example of forgotten graves found on a golf course.

“I’ve mapped another historic unmarked cemetery like this on a golf course at an Air Force base, when we were partnered with them. So, this is absolutely not an anomaly, this is not an outlier, a cemetery like this,” Shanks said. “There are hundreds of these cemeteries across the state of Florida, potentially even in the thousands.”

Meanwhile at the golf course, all parties involved say they want to see an appropriate memorial to the, until now, forgotten gravesite. Though, details on what a memorial or marker would look like are still in the works. Delaitre Hollinger says there are many ways the cemetery could be memorialized.

“I would like to see this seventh hole removed, I would like to see this golf cart path removed, I’d like to see this tee removed, and I’d like to see us fence off the area where it’s been determined that there are bodies buried,” Hollinger said.

He'd also like to see a historical marker go up. Revell estimates there will be a plan for that drawn up this year.