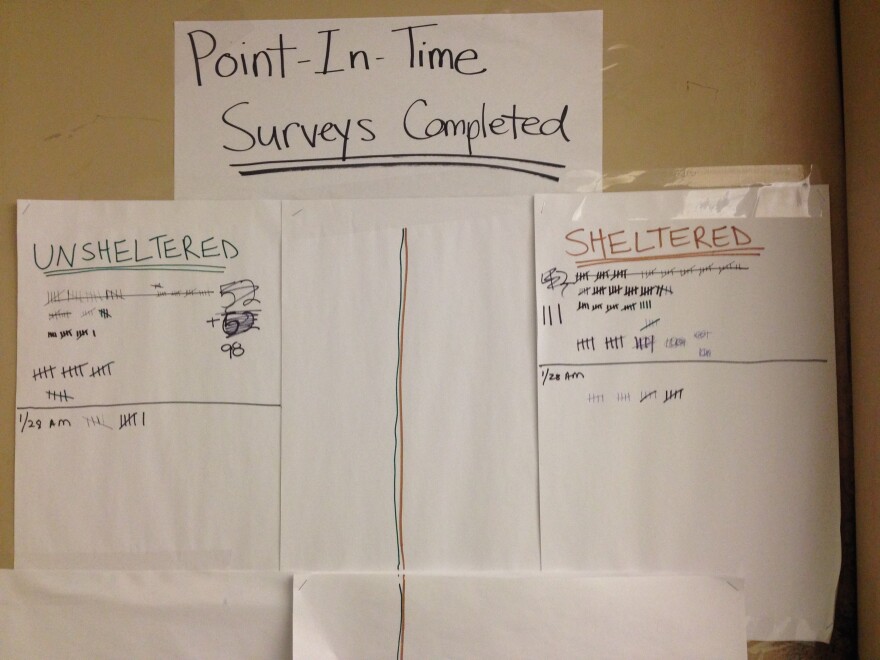

Across the country this week, volunteers conducted what’s known as the point-in-time homelessness count. WFSU joined one Tallahassee group as they tried to find people living without shelter in Florida’s capital city.

At 5:15 p.m. on Tuesday, about 30 volunteers huddled in a side office at the Big Bend Homeless Coalition cafeteria.

Outside it had just started pouring rain. One of the team leaders, Vicki Butler, had just come in from an all-day shift and she was about to go back out for the night shift.

“We’re just before delirious. We’ve been up for a few days at this point,” she says.

Butler tells volunteer coordinator David Langgle-Martin her team’s plan has changed.

“There’s no way I’m going be able to talk to people in a camp. It’s just raining too hard,” she says. “We’re going to have to stay in. We’re going to have to just do shelters. It’s the only way.”

All over the U.S., the point-in-time homelessness count happens at the end of January. Tallahassee’s effort spans three days and requires the help of each of the volunteers. Doug Marsh is a designated photographer: After talking to homeless people he takes their picture to prevent duplication.

“’Cause I’m able. You know, some people aren’t. So, you know, you have to look at the ability of the people that can do it, you know. And everybody can’t do that. So, the people that are able to do that need to volunteer to do things,” he says.

Lindsay Greene says she came because she heard about the homeless census in a Florida State University social work class.

“I think this will give me a good experience in working with people who are dealing with very unique struggles and get a better idea of the homeless community living in Tallahassee because I am a part of this community as well,” she says.

Another volunteer is stapling together survey packets the workers will take to shelters and camps. Before getting counted, people must agree to answer questions about their needs and living conditions. They’re often compensated with a $5 restaurant gift card.

As the troops gather around their team leaders, Langgle-Martin is verifying the next day’s weather forecast: Tallahassee is expecting its first snow in 25 years. Finally, he decides to call off the final morning of counting.

“Since we can’t go out in the morning, that means that we lose potentially a lot of people that we were planning on seeing in the morning,” he says.

He says between six and 10 camp sites were on the list. Now the only hope of surveying their inhabitants is if those people go to an emergency shelter for the night. Workers here estimate the surveyors find at most two-thirds of the area’s actual homeless population. And sometimes, as we’ll see in a minute, it’s because people don’t want to be counted.

By now, the rain’s let up enough that Vicki Butler decides to take her two volunteers in search of a campsite she thinks she saw earlier. It’s behind a popular shopping plaza.

She asks them, “How do you guys do with climbing hills?”

As she approaches the camp, she calls, “Hey, guys, I’m from the Big Bend Homeless Coalition We’re doing surveys for the point-in-time count. I’ve got a $5 gift card.”

The people at the camp say no.

“All right, buddy. You need blankets?” she asks. She then warns them of the possible snow. They say they’re OK. She walks back to her truck.

The two people at the camp won’t be counted because they refused the survey. But Butler says she doesn’t blame them for not trusting the rest of society.

“The homeless population gets brutalized for being homeless. Because that guy’s up there, somebody could come burn down his tent. Somebody could beat him up. I had a client that got beat over the head with a baseball bat because he was asleep in a park. That really happened,” she says.

Whether it’s because people refuse to be surveyed or volunteers simply don’t find them, Big Bend Homeless Coalition employees say the numbers will never truly reflect the area’s homeless population. And that has an impact on the local agencies that provide services to this segment of society.

Despite the difficulties, Butler says the point in time count is good for the Homeless Coalition.

“The count’s fantastic, for a number of reasons – one we’re able to meet people where they are. Y’know it’s really important to, if you’re in need you may not come to me, but if I can meet you where you are, then you see that I’m genuine, I’m trying, and y’know I want to be here because I want to help you,” Butler says.

Butler also says the counts help the Coalition find out what resources people need, where services can be improved, and which people are most vulnerable. But if people can’t be reached, the Coalition can’t offer these services. So why do the counts at the end of January when bad weather can get in the way, as it did this year?

Actually, Housing and Urban Development Acting Assistant Secretary Mark Johnston says bad weather is the one of the main reasons for conducting the count in January.

“In many communities”, Johnston says, “they’re in northern regions where it gets really cold in January relative to the summer, so you’d have more people seeking to get into a shelter and therefore more likely to be counted. So, the rationale really was to maximize the number of people that we find who are homeless.”

And while the point in time count is a factor in determining the funding agencies will receive, Johnston says it isn’t the only one.

“There are a whole host of scoring factors that we use for funding, and the number of homeless persons is a very, very minor element for selection and grant award,” Johnston says.

Otherwise, there would be an incentive for agencies to boost their counts because more people would mean more money. It’d be fraud, but it’d be a Robin Hood-style fraud. Johnston says that’s why there are nearly 60 different factors that go into determining funding.

The point in time count is a snapshot – it may not be the whole story, but as Johnston says, it does give local agencies vital information they can use in the coming year.

“The real value of the point in time count is to understand the nature of their problem”

Back in the parking lot, Vicki Butler is thinking about where she can go next. The rain is still coming down but it’s lighter now. In the cafeteria before leaving, Butler said she wouldn’t let it get in the way.

“Just have to go with it and hope for the best,” Butler says, “that’s really all you can do. Hopefully we know enough about the population to know where to meet them, and hopefully they trust us enough because they see us, to talk to us.”

With two refusals to start the night, Butler and two volunteers head off to see if they might have better luck elsewhere, hoping to get an idea of the challenges they’ll face in the coming year.