Martin Luther King Day is an opportunity to commemorate one of our country’s greatest national figures, but it’s also a chance to recognize the civil rights movement he shepherded. Florida lawmakers are working on a measure to rename a Broward County beach in honor of two local civil rights leaders.

When did segregation end? Brown v. Board of Education, right? History tends to flatten out like that—with a bit of distance and at a glance, broad societal changes are reduced to a date. But in reality, Brown was just the beginning.

William Crawford points to the 1960 film Where the Boys Are. “So you have this all white movie,” he says, “with thousands and thousands of college kids descending on Fort Lauderdale in 1960.”

And Crawford says the movie is important not just as a picture of what the beach looked like at the time, but also how it was policed.

“The college invasions were becoming so obnoxious that the city commission passed a law—an ordinance—that made it a crime for you to be a rioter,” Crawford says. “A rioter on the beaches of Fort Lauderdale.”

So, let’s step back a few years. Here’s Hollywood Democratic Representative Evan Jenne.

“On May 14, 1946 a delegation from the Negro Professional and Businessmen’s League petitioned the Broward county commissioners seeking a public bathing beach in Broward County,” Rep. Evan Jenne (D-Hollywood) says. “In 1954, the county finally acquired a barrier island site designated it for segregation, and promised to make the beach accessible by a road that was never built.”

“Let’s make that clear,” he says, “they had to use a boat to get to the only beach they were allowed to use in Broward County.”

Jenne’s wrong about the road—the city did build it, it just didn’t do so until the after the beaches integrated. Also, it’s worth noting the city purchased that beach after the Brown decision. But in 1961, seven years after that purchase, there was still no road access.

“In response, Eula Johnson, Dr. Von Mizell and many others led a series of protests—wade-ins—on all-white public beaches,” Jenne says.

Both were Broward county civil rights leaders and Eula Johnson was president of the local chapter of the NAACP. Jenne is pushing a measure that would rename the beach after Johnson and Mizell.

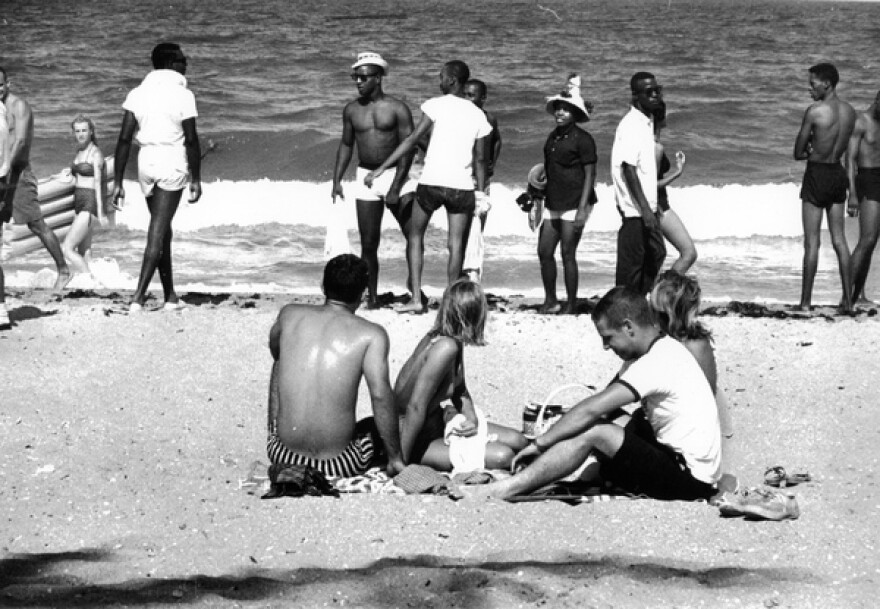

The wade-ins began July 4, 1961.

“The first wade in had seven people,” Crawford says. “Seven people. And on a good day, a Sunday, the beach would have 14,000 white people.”

Even so, local authorities attempted to stamp out the demonstrations by arresting protestors under the city’s riot ordinance. A year later a federal court found against the city.

“So we still had to fight that fight in Broward County and it wasn’t just in integrated our beaches, but our school system too, as well,” Rep. Bobby DuBose (D-Fort Lauderdale) says, “and Eula Johnson and Von D. played a major role in that as well.”

In addition to representing Fort Lauderdale, DuBose is a former city commissioner. He actually oversaw the city’s centennial.

“It was the fiftieth anniversary of the wade-ins so we did a re-enactment,” DuBose says.

Jenne’s measure renaming the beach passed its first committee last week.