Some bills die near the finish line, but some never quite make it out of the gate. A bill to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment died without a hearing yet again.

Disparities between men and women have been an ongoing feature in national politics, with a new story roiling to the surface seemingly every few weeks. Despite the recent ubiquity of this conversation, it’s really far from new.

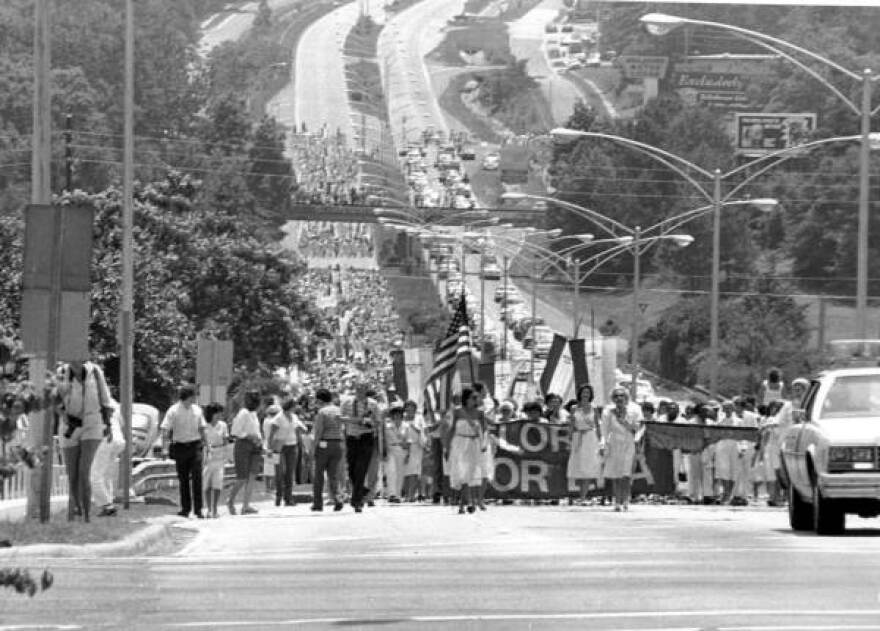

In 1982, then Florida Gov. Bob Graham convened a special session to consider ratification for the Equal Rights Amendment or ERA. It’s an idea that’s been around since the 1920s, and in 1972 Congress sent the amendment to the states for ratification. The Florida House approved it a total of four times—in 1972, 1975, 1979, and then one last time in Graham’s 1982 special session.

But it was a different story in the Senate.

“The wording of the amendment, just for your edification, is: ‘Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex,” Rep. Lori Berman (D-Lantana) says. “That is the entire wording of the amendment.”

For the past five years, Berman has filed legislation to ratify the ERA, and in those five years her bill has yet to get a vote.

Part of the reason why the ERA doesn’t get much of a hearing is that it pits social conservatives against social liberals. Early on, many Republicans supported the measure. But in the mid-seventies the party began to shift, and its members began embracing a more socially conservative outlook. But the other reason is many believe the ERA is already dead.

“There is one exception of an amendment that was passed something like 200 years afterwards so I think that even though we have a time limit, there could be some legislative action that could extend the time period and we could go beyond that,” Berman says.

Which amendment is that? It’s the 27th amendment and it was passed by a guy named Gregory Watson.

Back in 1982, Watson was an undergraduate student at University of Texas at Austin. His professor asked the class to write a paper on a governmental process, and Watson was actually planning to write about the ERA’s attempted ratification.

Until he came across a book that discussed earlier failed amendments.

“This one particular amendment from the year 1789 immediately stood out to me,” Watson says, “and it said that when members of Congress want to give themselves a pay raise, they must stand for reelection first before they receive the pay raise.”

Watson changed course. Unlike the ERA, this amendment had no date attached. That’s because Congress didn’t start attaching deadlines until 1917. Watson wrote up his paper, arguing the nearly two century old amendment was still ripe for passage.

He got a C.

“And so that’s when I decided I was going to get the amendment ratified,” Watson says.

He started writing letters, and the very next year—1983—the amendment came up in the Maine legislature. Watson was off and running.

In May of 1992 the national archivist added Watson’s amendment to the Constitution, and there hasn’t been another one since. So, what does Watson think about the ERA’s deadline?

“If you look at the actual text of Article V of the U.S. Constitution, nowhere do you find in Article V, any mention of a deadline,” Watson says.

The deadline actually comes from a Supreme Court decision. In 1921, the justices ruled Congress could impose a cutoff—but in that case the date was in the text of the amendment. The ERA’s isn’t. That gives activists like Helene de Bossiere-Swanson a sliver of hope.

“With the new three state strategy in play,” de Bossiere-Swanson says, “meaning that we could go back to just needing three more states, I have been actively working on bringing senators and congressmen on board.”

Her idea focuses on repealing the earlier deadline, and then continuing the ratification process at the state level. She’s walking across the country to visit the capitol of every state that has yet to ratify.

But even if the timeline is thrown out, Watson says there’s another hurdle to publishing.

“There were states that passed it, and then later rescinded it.” Watson says. “Well, can a state rescind a prior ratification? I don’t know. That question, unlike the deadline question, was never put to the federal courts.”

Watson believes adding the ERA to the Constitution would likely spark off a major court battle—and it’s one that he’d welcome, if for no other reason than personal curiosity. He admits piecemeal efforts toward equal treatment in recent years have taken some of the wind out of the ERA’s sails, but he says there’s still a chance of its passage.

And while it may have died a silent death in the Florida legislature this year, Rep. Berman seems ready to file it again in 2016.

“I continue to hold out hope. Some of the other states are still looking at it, and hopefully if Florida took some action on it, I think it could lead to a nationwide trend,” Berman says.

But even if Berman is successful, the ERA would still need at least two more states. Until that happens, headlines about the gender gap probably aren’t going anywhere.