Imagine publishing a list of all of your recent sexual partners in the local paper. That was what one 2001 Florida law, enacted under then-Gov. Jeb Bush, required of some women in the state.

Huffington Post reporter Laura Bassett brought the so-called Scarlet Letter law to national attention in a Tuesday piece. Here's a rundown of what exactly that law did, and why it was passed in the first place.

What did the law do?

The law in question was a 2001 overhaul of the state's adoption regulations. Bush wrote shortly after the Legislature passed the bill that the law was intended to bring more "certainty" into adoptions. The goal was to "provide greater finality once the adoption is approved, and to avoid circumstances where future challenges to the adoption disrupt the life of the child."

One way to accomplish that was to balance the "rights and responsibilities" of both birth parents, as well as the adoptive parents, Bush wrote. To the end of preserving the rights of a birth father, the law required a woman who didn't know who had fathered her child to put a notice in the newspaper so that a potential father could see it and respond before that child was put up for adoption.

The published notice would have to contain an extensive list of personal information, including potential cities and dates where the act of conception might have occurred, according to a 2004 Notre Dame Law Review article:

"The notice ... must contain a physical description, including, but not limited to age, race, hair and eye color, and approximate height and weight of the minor's mother and of any person the mother reasonably believes may be the father; the minor's date of birth; and any date and city, including the county and state in which the city is located, in which conception may have occurred."

And it wasn't a one-time ad — it had to run once a week for a month, at the expense of either the mother or the people who wanted to adopt the baby, as that 2004 article explains.

Because the law required women to put their sexual history on display, it became known as the "Scarlet Letter law," after the Nathaniel Hawthorne novel in which the protagonist must wear a red A on her dress to signify that she had committed adultery.

Did Jeb Bush want women to be shamed for their sexual activity?

It's true that years before the law was passed (and before Bush was even governor), Bush had bemoaned what he saw as a lack of social stigma for men and women alike having children outside of marriage. In his 1995 book, Profiles in Character, he wrote (in a chapter with the dark title, "The Restoration of Shame"), as Bassett reports:

"One of the reasons more young women are giving birth out of wedlock and more young men are walking away from their paternal obligations is that there is no longer a stigma attached to this behavior, no reason to feel shame."

In that book, Bassett also writes, Bush invokes The Scarlet Letter (approvingly) as an example of how society had once condemned people for sexual impropriety.

Those may have been his general thoughts, but it's also true that he didn't wholeheartedly approve of the adoption law. He thought it put too much of the onus on the birth mother to find the father, as he wrote in a letter to Secretary of State Katherine Harris, upon letting the bill pass into law without signing it.

"House Bill 141 does have its deficiencies," he wrote. "Foremost, in its effort to strike the appropriate balance between rights and responsibilities, there is a shortage of responsibility on behalf of the birth father that could be corrected by requiring some proactive conduct on his part."

In fact, immediately after he let the bill become law, Bush was advocating for fixes to it. The Florida House almost immediately passed a law that he considered a "better alternative." It cut back on women's reporting requirements and established a paternity registry, for example. These are state-maintained databases that allowed a man to register if he believed he might have fathered a child. Then, if that child were ever put up for adoption, the father would have been notified and he could have a say in the proceedings.

(A Bush spokesperson has not yet responded to an NPR request for comment.)

Is the law still in effect?

Nope. Two years after the law passed, Bush signed a replacement law that addressed many of his 2001 concerns, including instituting a paternity registry. This happened just weeks after a Florida appellate panel declared the provision requiring women to list their sexual encounters unconstitutional because it was deemed an invasion of privacy, as the L.A. Times reported at the time.

So what does this do to his presidential candidacy?

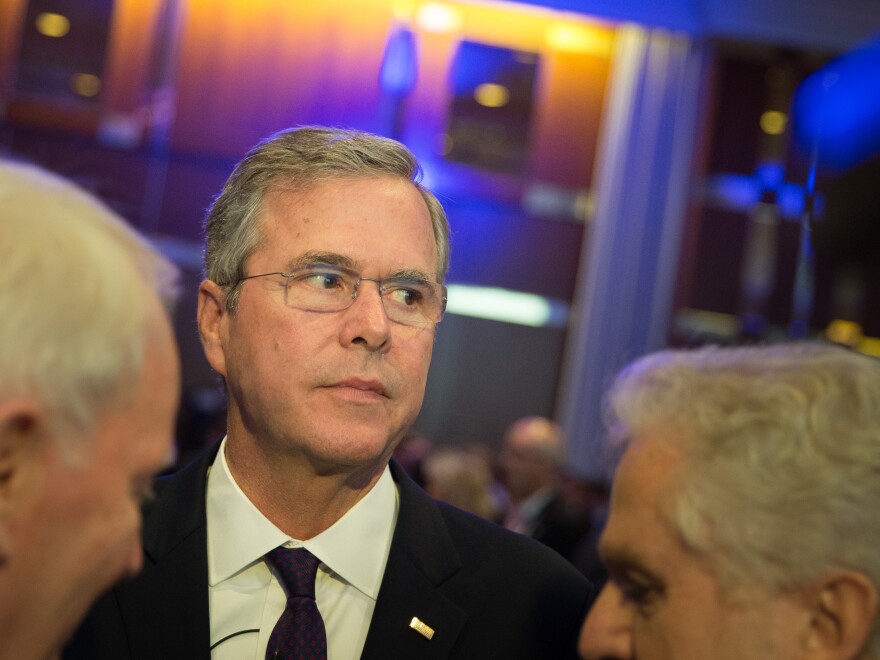

This early in the game, it's easy to overestimate how consequential pretty much anything is that happens. After all, Bush is expected to only formally announce his candidacy on June 15.

However, it's true that this comes during a rough few days for the fledgling campaign. In a surprise move this week, Bush reconfigured his campaign staff. And his superPAC, Right to Rise, looks unlikely to raise the $100 million it had expected in the first half of 2015, as the Washington Post's Matea Gold and Tom Hamburger report.

Looking at the bigger picture, it's possible the issue could come back in a general election, if he gets through the primary. Democrats are pushing it, because it plays into a common narrative about the Republican Party as both parties try to appeal to women.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.